Why do people kill each other? It’s a question that I think

about, perhaps too often. Greed, jealousy, revenge? To solve a sticky relationship problem — such

as unwanted spouses who won’t go away on their own. Or maybe to end a loved one’s suffering? For the greater good? The crowded lifeboat

debate. But the other question is why

are so many others so curious about the subject? It’s not really a pleasant

subject.

I know that eating too many Pepperidge Farms Chesapeake

cookies is unhealthy and that to outsmart myself I must never buy more than one

bag at a time. I feel similarly about my

diet of crime fiction, especially on Saturday when, because I’m an anti-social

curmudgeon, I binge on true crime as served by “48 Hours,” “Dateline,” and “20/20.”

The long, drawn-out dramas chronicling human sadness cannot be that healthful

for the brain. But just as carrots and kale

cannot satisfy certain hungers, neither can mind-improving or soul-lifting

drama cure the apparent need for the seamy side of life.

For the most part, I’m not talking about wars or terrorism,

or even the collateral damage of an armed robbery, though understanding the

murderous psyche might help us there, but murders of a personal nature, where,

in some fashion, victim and perpetrator know each other or in instances when

the driving force behind the murder is mysterious in and of itself.

Murder. Movies are made of this. True-life murders are a

staple of small-screen, low-budget, but often riveting productions. They show

how dilemmas in the ordinary lives of ordinary people ratchet into

irretrievable acts of violence. The big-screen nonfiction dramas are usually

about people we all know because the media was obsessed with the crime or the

people involved, or because it reflects a larger theme.

|

| From the film, Swoon |

The court proceedings for two young men, Leopold and Loeb,

for the murder of a young student Bobby Franks in 1924, was billed as the

“trial of the century.” The kidnappers and victim were children of exceedingly

wealthy parents.

Loeb, obsessed with the

philosopher Friedrich Nietzche, had latched onto an interpretation of the “superman

principle,” that if you are smart enough, you are not bound by the laws

designed for ordinary humans.

Loeb thought

of himself smart enough and convinced Leopold, follower and lover, to commit

the perfect crime. It wasn’t perfect, apparently. The boys were on their way to

an almost certain death penalty. The most famous American attorney of this or

any time, Clarence Darrow represented the defense. Scandalous for its

homosexual overtones, the trial of he century was also one of the nation’s mot

important trials because of the capital punishment implications as well as its

philosophical “superman” backdrop. The Leopold & Loeb trial was made for

the cinema. The story inspired

three major films — Alfred Hitchcock’s

Rope,

Compulsion with Orson Welles, and

Swoon, which had spelled out the story’s gay component,

intentionally downplayed in previous versions.

|

| From the film, Reversal of Fortune |

Later, actor Jeremy Irons portrayed the social climbing

Claus Von Bulow in another torrid trial concerning the death of Von Bulow’s

wealthy, high-society wife, Sunny. Von Bulow was successfully defended by celebrity

lawyer Alan Dershowitz and was made into the movie,

Reversal of Fortune. The film was was a hit and Irons earned an

Academy Award for his portrayal of the ice-cold Von Bulow, who had well more

than his 15 minutes of fame.

In the 1950s, the murder of

Dr. Sam Sheppard’s pregnant wife

dominated the media. The surgeon claimed he was struck and knocked unconscious,

but that he saw the murderer in a long coat leaving the scene of the crime. The

story was splashed all over the tabloids and the mainstream media followed.

Sheppard was eventually acquitted with help

of media favorite attorney, F. Lee Bailey.

Though no one claimed it was Sheppard’s story there is little doubt the

crime and the mystery surrounding it inspired the incredibly popular film,

The Fugitive, and the successful TV series

also bearing that name.

|

| From the TV series, The Fugiive |

There are other films based on real-life murders. The lesser

known

Prick Up Your Ears —

a film based on the book of the same name—

tells the story of naughty British playwright

Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell,

his lover and sometimes writing partner, who hammered Orton to death before

killing himself in their claustrophobically tiny apartment, a room almost too

small for one.

Why has always been the most important question of the

journalistic “w’s” for me. I’m told I drove my elementary school teachers crazy

with that question. I continue. Again, I’m not talking about wars, revolutions

or drive-bys. That’s a good question as well. But mine is: Why do people kill people one-on-one? Is there

any unified theory explaining why people do this? They seem to rarely get away with it. Perhaps

there is no simple answer. However, I’d like to propose one.

Self-preservation.

Not necessarily self-defense as we understand it; but self-preservation

in the broadest sense. Preserving the self can include doing what’s necessary

to preserve one’s perception of self or pursuing the self as one wants to

perceive it or be perceived by others. In the case of Von Bulow, we have a

fellow who grew up in the shadow of wealth and privilege, yet always dependent

upon another for his station in life. His family served the wealthy. He served Jean Paul Getty as an assistant. He married into wealth and privilege, but was

always privilege’s husband. He was acquitted of attempted murder by insulin injection,

(his wife lived on in a coma). The

young, handsome, respected Dr. Sheppard was about to have a child, which would

have inhibited any choice to live a more adventurous life perhaps an alternate

fantasy during a mid-life crisis to that of a quiet, reserved family man, bound

by the conventions of that status. After

acquittal, the good doctor became a professional wrestler.

Did Leopold and Loeb have to prove to themselves that they

were smarter than anyone else to justify their belief they occupied a rarefied

space superior to that of ordinary mortals? It wasn’t a matter of preservation

of the body, the physical self, but that special place they thought they

occupied. They failed miserably. The irony is that if they had achieved or were

deserving of the “superman,” or “overman” label as Nietzsche defined it, they

would never have sought it or felt the need to prove it. The death of Bobby Franks was completely

senseless. The trial itself wasn’t one of guilt or innocence. The evidence was

clear. The boys confessed. No perfect crime for them. Darrow’s job wasn’t easy

but the goal was simple: to prevent the two self-proclaimed geniuses from being

sentenced to death. He did, though Loeb was stabbed to death in prison. Leopold

was eventually paroled and surprisingly made serious contributions to humanity

in ways Nietzsche might have actually recognized as the work of the Overman he

described.

|

| From the film, Prick Up Your Ears |

Why did Halliwell kill Orton? They were partners/lovers,

co-conspirators in life. Because their

identities were intertwined and for Halliwell interdependent. Orton’s success pulled his friend into the

spotlight. Soon it was not Orton and

Halliwell, but Orton and his increasingly nameless friend, and then Orton. Only

Orton. Orton further threatened their

shared identity by going his own way not only as a writer, but by eventually

finding another lover. What did that

leave Halliwell? They died together,

within moments of each other. Was Halliwell not trying to protect himself

despite the fact he was the man with the hammer and the overdose? For

Halliwell, perhaps it wasn’t murder-suicide, but only suicide. Hadn’t he, in his

perception, only killed himself for his failure to achieve a self?

Certainly self-preservation is built in. We will do

everything we can to save our own lives.

Most would do all they can to save the lives of loved ones. One can make

the case that we could not live with ourselves

if we didn’t. I think that instinct, at

least for us humans who are self-conscious and who try to create meaning for

why we live, is basic to understanding why we kill. On the surface, it may be that someone

disrespected us, stole from us, had something (money, position, love) that we

felt was necessary for our survival that provides motive. But the base need

always relates to survival of the self as we define it or understand it to be. At least that’s the theory.

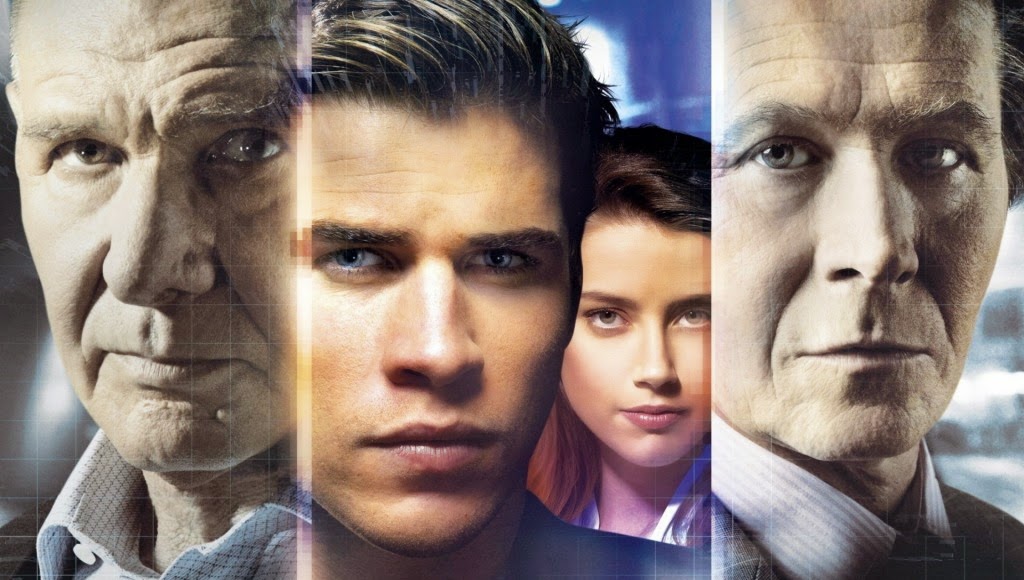

Good People — Just a touch of greed. The tenant in a run-down

home of a struggling young couple (James

Franco and Kate Hudson) dies,

leaving behind a pile of dangerous dough, residue from a double double-crossed

dope deal. The criminal doesn’t appear

to have a next of kin and the cops have cleared his abode without discovering

the stash. After a brief wait, the couple, (nice kids) decide to keep the money. After all, what cold possibly go wrong? As it

turns out there are two gangs who had been screwed over, and the police have

more than a professional interest. There’s really no way they can do the right

thing once things get going. Again, the plot is not exactly new. Most plots aren’t. What we’re interested in

here is how can two ordinary people deal with all the powerful and evil forces

mounted against them and each other.

There is a certain amount of suspense.

However I kept thinking about Home

Alone and how much more effective Macaulay

Culkin was in his dealings against his home invaders. Tom

Wilkinson adds a more realistic dimension to the action, but this film,

like Paranoia, wasn’t really ready

for the big screen. But again, while you

will not be forced into hours of distressed thought about the meaning of life,

the goodness or badness of humanity, there are entertaining moments. Good People was directed by Henrik Ruben Genz and based on a book

by the same name, written by Marcus

Sakey.

Good People — Just a touch of greed. The tenant in a run-down

home of a struggling young couple (James

Franco and Kate Hudson) dies,

leaving behind a pile of dangerous dough, residue from a double double-crossed

dope deal. The criminal doesn’t appear

to have a next of kin and the cops have cleared his abode without discovering

the stash. After a brief wait, the couple, (nice kids) decide to keep the money. After all, what cold possibly go wrong? As it

turns out there are two gangs who had been screwed over, and the police have

more than a professional interest. There’s really no way they can do the right

thing once things get going. Again, the plot is not exactly new. Most plots aren’t. What we’re interested in

here is how can two ordinary people deal with all the powerful and evil forces

mounted against them and each other.

There is a certain amount of suspense.

However I kept thinking about Home

Alone and how much more effective Macaulay

Culkin was in his dealings against his home invaders. Tom

Wilkinson adds a more realistic dimension to the action, but this film,

like Paranoia, wasn’t really ready

for the big screen. But again, while you

will not be forced into hours of distressed thought about the meaning of life,

the goodness or badness of humanity, there are entertaining moments. Good People was directed by Henrik Ruben Genz and based on a book

by the same name, written by Marcus

Sakey.