Often I put two movies together because of some tangible

similarity — plot, character, cinematic style, even setting. These two are none of the above. The only thing they have in common is that

they are really good. But they couldn’t

be more different

Often I put two movies together because of some tangible

similarity — plot, character, cinematic style, even setting. These two are none of the above. The only thing they have in common is that

they are really good. But they couldn’t

be more differentSunday, January 4, 2015

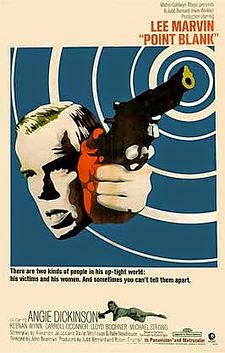

Film Pairings — Two Very Different, And Nearly Flawless Films

Often I put two movies together because of some tangible

similarity — plot, character, cinematic style, even setting. These two are none of the above. The only thing they have in common is that

they are really good. But they couldn’t

be more different

Often I put two movies together because of some tangible

similarity — plot, character, cinematic style, even setting. These two are none of the above. The only thing they have in common is that

they are really good. But they couldn’t

be more differentWednesday, September 10, 2014

Book Notes — Ten Books That Served As Courses in Life And Writing

I first learned of this “tag-a-friend” project on the crime

fiction web blog, Rapsheet, which I go to every morning to accompany my first

cup of coffee of the day.

I first learned of this “tag-a-friend” project on the crime

fiction web blog, Rapsheet, which I go to every morning to accompany my first

cup of coffee of the day.  ★ Young Törless,

Robert Musil Musil wrote this prescient tale about the end

of innocence and the onset of adolescence while the Nazis were gathering their

evil forces in Europe. The book foresaw

the human capacity to force people to belong to a powerful group and to torture

those who don’t or can’t. Musil also

introduced me to his more famous contemporaries— Thomas Mann and Herman Hesse.

★ Young Törless,

Robert Musil Musil wrote this prescient tale about the end

of innocence and the onset of adolescence while the Nazis were gathering their

evil forces in Europe. The book foresaw

the human capacity to force people to belong to a powerful group and to torture

those who don’t or can’t. Musil also

introduced me to his more famous contemporaries— Thomas Mann and Herman Hesse. ★ Armies of the

Night/Miami And The Siege of Chicago, Norman Mailer I’m not sure this is history as fiction or

fiction as history, but Mailer’s journalistic style strikes me as a valuable writer’s

resource. These two books, observations of our government’s bad behavior, were

part of a new kind of writing that many well-known authors claimed to invent,

including Truman Capote with his celebrated, In Cold Blood.

★ Armies of the

Night/Miami And The Siege of Chicago, Norman Mailer I’m not sure this is history as fiction or

fiction as history, but Mailer’s journalistic style strikes me as a valuable writer’s

resource. These two books, observations of our government’s bad behavior, were

part of a new kind of writing that many well-known authors claimed to invent,

including Truman Capote with his celebrated, In Cold Blood. ★ Clarence Darrow for

the Defense, Irving Stone I was a strange little kid. I didn’t have any real heroes until this book

came along and I got to know something about Clarence Darrow. A little later I discovered a second hero – Cassius

Marcellus Clay (not the boxer, the abolitionist). Both gained a significant amount of power and

stature. Both were deeply flawed, but

both were willing to risk everything to pursue causes they believed in.

★ Clarence Darrow for

the Defense, Irving Stone I was a strange little kid. I didn’t have any real heroes until this book

came along and I got to know something about Clarence Darrow. A little later I discovered a second hero – Cassius

Marcellus Clay (not the boxer, the abolitionist). Both gained a significant amount of power and

stature. Both were deeply flawed, but

both were willing to risk everything to pursue causes they believed in.Friday, December 16, 2011

Film Pairing — The Lighter Side of Espionage

Espionage. What a rich source of mystery and intrigue. I remember reading and then watching The Spy Who Came in from the Cold by John le Carré. There was the riveting Gorky Park by Martin Cruz Smith. And of course, Ian Fleming’s James Bond. I read every book by Fleming and have seen nearly every film. The movies seemed to take on the character of the actors who played Bond. Sean Connery played Bond seriously, with the driest of humor. Roger Moore came at it a little more tongue in cheek — he was in on the joke — maybe adding a bit of wonderful British silliness. And Pierce Brosnan walked a line somewhere in between as the screenplays became more about special effects and were more preposterous. The new guy, Daniel Craig is great, perhaps bringing Bond more gravitas than Connery.

Espionage. What a rich source of mystery and intrigue. I remember reading and then watching The Spy Who Came in from the Cold by John le Carré. There was the riveting Gorky Park by Martin Cruz Smith. And of course, Ian Fleming’s James Bond. I read every book by Fleming and have seen nearly every film. The movies seemed to take on the character of the actors who played Bond. Sean Connery played Bond seriously, with the driest of humor. Roger Moore came at it a little more tongue in cheek — he was in on the joke — maybe adding a bit of wonderful British silliness. And Pierce Brosnan walked a line somewhere in between as the screenplays became more about special effects and were more preposterous. The new guy, Daniel Craig is great, perhaps bringing Bond more gravitas than Connery. On the other hand, “preposterous” isn’t always a bad thing. In 1958, former real-life secret agent Graham Greene wrote Our Man in Havana, which poked fun at the inefficiencies of his country’s intelligence operation. In 1959, he wrote the screenplay, which was set not long before the fall of Fulgenico Batista’s Cuba and Fidel Castro’s successful takeover. The movie, in black and white, captures corrupt, pre-revolutionary Cuba and has an all-star cast — Alec Guinness, Noél Coward, Burl Ives, Maureen O’Hara, Ralph Richardson, and Ernie Kovacs.

Guinness plays an unassuming character who sells vacuum cleaners for a living. He is in need of money to support his daughter, over whom he dotes, and is convinced to act as a spy for the British so she can have a first-class education. His spy mentor is an ineffectual, but stubborn dandy played by Coward. In order to meet his new employer’s expectations, the vacuum cleaner salesman finds it helpful to make up stories about threats to Britain to prove his worth, which in turn inflates his income. Seems harmless enough. But, of course, it isn’t.

The Tailor of Panama (2001) is based on a novel by John le Carré. The parallels between the novelists, the books — and the subsequent movies are strikingly similar, yet expected. John le Carré, who wrote the Tailor of Panama, made no secret that his novel was inspired (probably a little more than “inspired”) by Greene’s. Like Greene, he also co-wrote the screenplay for the film based on his own book. Also, like Greene, he spent part of his life as a secret agent (MI5). The movie, which changes the scenery slightly — though still in a hot, tropical climate — also changes the times. We move to the post Panama Canal turnover for this film, but the politics in the era of Manuel Noriega are still iffy. Obviously Western powers are interested in knowing what’s going on and are willing to pay dearly for information, however made-up it might be.

In this case a tailor is recruited to provide the local spying. Geoffrey Rush plays the Guinness role. Brosnan, who might have taken smugness to an entirely unparalleled level, gave a far more heavy-handed interpretation than Coward’s light and subtle (by comparison anyway) portrayal of corruption. Jamie Lee Curtis and Brendan Gleeson also star.

What these two comedies have in common, besides the Graham Greene novel as inspiration, is that its silly believability stems not so much from “it could happen,” to “how many times this sort of thing has happened.” The British and Americans have fumbled foreign affairs for centuries. The West has installed and removed dictators, supported and withdrawn support for insurgents and undertaken regime changes, invasions and denials. We have, in a way that mirrors the Greene tale, believed a local agent’s contention that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction with a photo of an ice cream truck as proof. How many times have our (and our British cousins) interference made a mess of things? Chile anyone? Then there was that nice fellow, the Shah of Iran!

In the spirit of the two movies: Daiquiris all around! And I’ll begin the first draft of Our Good Humor Man in Bagdad.