I’m rummaging these days. What I turned up in my excursion

through old photos, magazines, letters and books is a little gem — a short

article by the very talented writer Gay Talese that had been inserted into the April 1966 issue of Esquire. It was called “The Greatest Story Ever Told: Frank Sinatra Has A Cold.”

I’m rummaging these days. What I turned up in my excursion

through old photos, magazines, letters and books is a little gem — a short

article by the very talented writer Gay Talese that had been inserted into the April 1966 issue of Esquire. It was called “The Greatest Story Ever Told: Frank Sinatra Has A Cold.”

It’s a long short story of maybe 10,000 words based on Mr.

Talese’s observations during a few days leading up to the legendary singer’s

50th birthday. It is a revealing profile written in a style that combined

journalism and fiction, a form touted as a new way of writing, the origin of

which is in dispute. Truman Capote

(In Cold Blood), Norman Mailer (Armies of the Night) and Talese himself lay claim to its invention.

I’m a fan of Frank

Sinatra, his music (“My Way” and “Strangers in the Night”) and his movies.

He was extraordinary in From Here To

Eternity, The Man With A Golden Arm and

The Manchurian Candidate. Though less revered as films, he was also

believable and charismatic in such low-budget productions as The Detective and Lady in Cement. He hit the top as both a singer and actor. His

tough–guy antics and supposedly torrid romances also fed the gossip mongers while

the rumors of his mob connections not only added to his larger-than-life persona

but, true or not, gave him a great deal of personal power The sad fact was,

that despite his talent the man was a bully.

Talese painted a rich, three-dimensional profile of a man

by, for the most part, by recounting a few hours in a bar and a few more in a

recording session. The people around him were either in love with him or

frightened of him or more likely, both. In almost all cases, whether he knew them

or not, he made them nervous. Talese captured the essence man who may have

wanted to be feared more than loved in what might be casual observations,

condensing a life time into a few pages.

Most of us — of a certain age — cannot enter the story

without prejudice. Sinatra’s reputation for being unpredictable — throwing a

drink at someone or the whole bottle for example or simply punching them

without warning or provocation — preceded him wherever he went. There was a

sense that if he didn’t belong to the mob, he had one of his own. And it took

next to nothing to piss him off. Though not part of this account, the singer

once gave a waiter $50 to punch writer Dominick

Dunne who was sitting a few tables away. The waiter did what he was told.

The money probably had nothing to do with why the young man’s fist found

Dunne’s face. In another account, a drunk and angry Sinatra tried to set the

Las Vegas Sands Casino on fire.

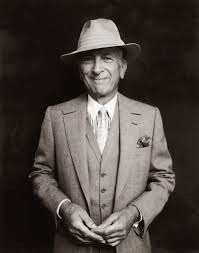

|

| Gay Talese |

But as the Talese story goes, Sinatra decided to leave the

main bar and go to the back room where a few folks were playing pool. When the door opened, peope stopped what they

were doing. The chairman had arrived.

Should they stand at attention?

Maybe salute? However, one guy

didn’t seem interested in Sinatra’s arrival, It was writer Harlan Ellison (author of A

Boy And His Dog among many classic books and screenplays). Ellison’s profound indifference was

provocative.

Sinatra confronted Ellison.

Perhaps because he couldn’t think of a legitimate reason to be upset or

a better insult to proffer on such short notice, Sinatra said he didn’t like

Ellison’s boots. Ellison suggested that

the singer’s likes and dislikes weren’t important to him. After a few moments of nervous silence, the

room began to clear. Even tough ball-player Leo Durocher discreetly put down his cue stick and disappeared.

|

| Harlan Ellison |

“Why do you persist in tormenting me? Sinatra asked Ellison

softly — “almost a plea,” Talese remembered. Whatever it was, or could have been, was over.

When I first moved to San Francisco, I found a room just off

Haight Street on Stanyan. It was post “Summer of Love.” In fact it was well past the “wear a flower

in your hair” era. The marijuana was

laced with Angel Dust PCP), hard stuff, mean stuff. The neighborhood appeared to have been

ransacked, gray. Store fronts were closed and the whole neighborhood was

dismal, a war zone. The folks who roamed there were either vacant-eyed lost

souls or toughs looking for someone to roll.

A friend, who calculated that my blond hair, soft face and Midwest

attitude would reveal the mark of the mark, gave me some advice. He said that if I ever found myself in a

dangerous situation, I should just act crazy. “Everybody’s afraid of crazy,” he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment